If

there’s a little known hero of the Civil War, it has to be Dr. Jonathan

Letterman. I was reminded of that

recently when the founder of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, Dr.

Gordon Dammann, gave a lecture on Dr. Letterman and his Letterman Plan. Maybe you’ve never heard Dr. Letterman’s name

before, but your life has probably been affected by his work. The Letterman Plan, which is a system for

treating and evacuating casualties from battlefields, is the basis for many aspects

of our modern military medicine, emergency medicine, and even disaster relief.

|

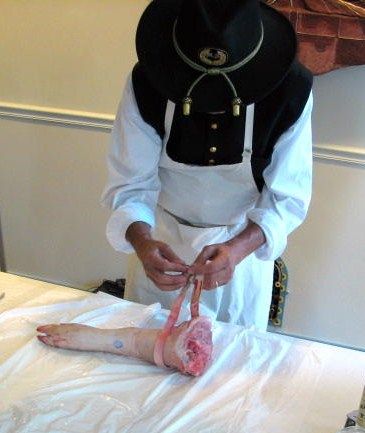

| Here is Dr. Dammann, talking about Dr. Letterman and his plan. I think this is one of his favorite topics! |

At the

start of the Civil War, there was no set procedure for removing wounded

soldiers from the battlefields. In some

cases, the wounded were left on the battlefield for over a week, which meant

that many of the men, who might have been saved, died from their wounds or from

exposure. While the army did have

ambulances which could transport the wounded soldiers, the ambulances were

under the control of the Quartermaster Department which procured and

distributed most of the supplies for the army.

As you might imagine, the ambulances were not always the top priority in

this system! In fact, there were instances

in which ambulances were appropriated to carry other supplies, or even personal

items.

In 1862, just

a few months prior to the Battle of Antietam, Major Jonathan Letterman was

named the Medical Director of the Union Army of the Potomac. His first step toward revamping the medical

system was to establish a separate Ambulance Corps. He gave control of the army

ambulances to the officers of the ambulance corps, he distributed ambulances to

each regiment, he had enlisted men trained to serve as ambulance drivers and

stretcher bearers, and he had the use of ambulance wagons for any non-medical

uses forbidden.

Letterman

also reorganized the system of medical treatment and field evacuation. He applied a triage system in which the

wounded were treated based on the severity of their wounds instead of the order

they arrived. He also established aid

stations on the battlefields, where medical officers could stabilize the

wounded soldiers and arrange for their transportation to a field hospital. The field hospitals were located near the

battlefields. It was here that the soldiers

received additional treatment, including emergency surgery if needed. If more long-term treatment was required, the

wounded were transported to the larger, more permanent hospitals which were

usually located in the cities.

The

Battle of Antietam, the bloodiest single day in American history, was the first

real test of Major Letterman’s new system.

It was a success. Even when faced

with over 23,000 casualties, his plan ensured that all of the wounded were removed

from the battlefield within 48 hours, which undoubtedly saved many lives. He continued to make changes and

improvements, and in 1864 his plan was made official by an Act of Congress.

|

| Though the equipment has

changed, the Letterman Plan is still in use today. |

I’ll

leave you with a quote from the NMCWM’s own website: Major General Paul Hawley,

Chief Surgeon of the European Theater in the Second World War, said of

Letterman, “I often wondered whether, had I been confronted with the primitive

system which Letterman fell heir to at the beginning of the Civil War, I could

have developed as good an organization as he did. I doubt it. There was not a

day during World War II that I did not thank God for Jonathan Letterman.”

|

| An 1862 photo of Major Letterman (first seated figure) and his staff in Warrenton, Virginia. Library of Congress image. |