There’s a story the Director of our museum

(George) likes to tell about overhearing two people on the street debating over

whether or not to visit the museum. The

wife was looking in the front window and commenting that she’d like to take the

tour. Her husband replied, “Civil War

medicine? It’s just a saw!” At that point, George stepped up and offered

to show them the museum, as well as how much more there was to Civil War

medicine than an amputation saw.

|

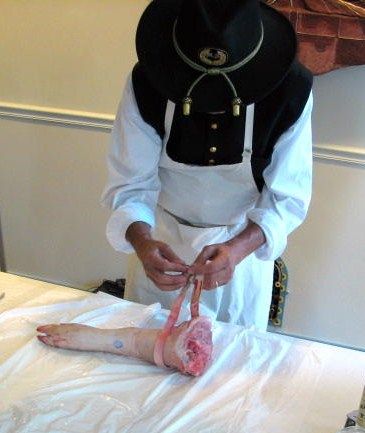

| Here is what most people associate with Civil War medicine - an amputation kit. This is a nice example of an amputation kit with a rosewood case and the basic instruments (including the saw!) needed to perform an amputation. |

Sadly, this has been the image of Civil

War medicine for quite some time. Even

during the war, the surgeons were judged to be “butchers” for performing so

many amputations. The image has

persisted through the years, and many people still have the idea that Civil War

surgeons were heartless and incompetent.

The simple truth is that these surgeons were saving lives in the best

way that the knowledge and technology of the time allowed.

There is no doubt that amputations were a big part of Civil War medicine though. So, let’s take a look at some of the instruments that were used.

|

This is the culprit responsible for the necessity of so many amputations - the Minié ball. These bullets caused tremendous damage to soft tissue and to bones. One medical textbook of the time describes the damage as

“….truly terrible; bones are ground almost to powder, muscles, ligaments, and tendons torn away, and parts otherwise so mutilated, that loss of life, certainly of limb, is almost an inevitable consequence.” |

|

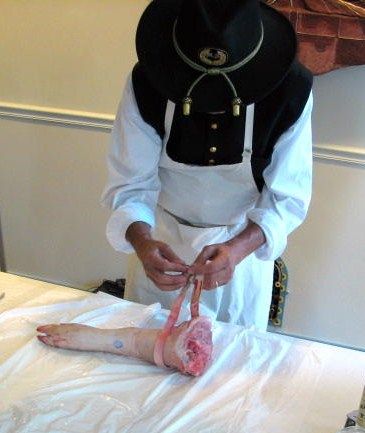

One of our volunteers is a present-day surgeon, even though he dresses as a Civil War surgeon at the museum! He took our Director, George, through the amputation process, using a pig leg.

Don’t worry; even though those instruments look old, they are actually reproductions of Civil War instruments. I wouldn’t let them use the real ones! |

|

| Normally the first step in an amputation was to anesthetize the patient, but obviously that was unnecessary for this“patient.” The next step would be to apply a tourniquet to the limb above the wound, to stop or slow the bleeding. |

|

| Here is an example of a Petit’s screw tourniquet, which would have been used in the Civil War. |

There were two main methods of amputation

used in the Civil War. The flap method

left flaps of skin and muscle which would be used to cover the stump at the

completion of the operation. A V-shaped

cut would be made, and then the bone would cut away a few inches above the

flaps. In a circular amputation, the

surgeon basically cut in a circle around the limb, would draw back the skin

slightly and then cut straight across the bone.

|

George uses an amputation knife to make the first incision through the skin and muscle. Afterwards, the skin and muscle will be pulled back slightly from the bone.

I will point out here that Civil War surgeons did not wear gloves. |

|

| This amputation knife is similar to the one being used in the photo above. Single-edged amputation knives were used for circular amputations. |

|

| This double-edged amputation knife is called a catlin. It was more commonly used in flap amputations. |

|

| The amputation saw was used just to cut through the bone. |

|

| This is a typical amputation saw with a “fishtail” handle. The checkered texture on the handle gave the user a better grip. Operating quickly was important. There was less chance of shock to the patient, and it allowed the surgeon to move on to the next patient quickly. Most amputations were done in less than ten minutes! |

|

| With the amputation completed, the surgeon would use a hooked instrument called a tenaculum to pull out the large blood vessels to be tied off. |

|

| Here is a closer view of a tenaculum. |

|

| This instrument, called a rongeur, would be used to remove any sharp edges from the bone before closing the wound. A bone file could be used to help smooth the bone too. |

|

| And finally, the flaps of skin would be sutured together. Often, an opening would be left to allow the wound to drain. Bandages would be applied to the stump. |

|

| Surgical needles haven’t changed much since the Civil War! |

To learn more about Civil War amputations

click here.

I’ll leave you with a quote from the medical director of the Army of the Potomac, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, who wrote in his report after the battle of Antietam,

“The surgery of these battle-fields has been pronounced butchery. Gross misrepresentations of the conduct of medical officers have been made and scattered broadcast over the country, causing deep and heart-rending anxiety to those who had friends or relatives in the army, who might at any moment require the services of a surgeon.

It is not to be supposed that there were no incompetent surgeons in the army. It is certainly true that there were; but these sweeping denunciations against a class of men who will favorably compare with the military surgeons of any country, because of the incompetency and short-comings of a few, are wrong, and do injustice to a body of men who have labored faithfully and well.”

Photos courtesy of the National

Museum of Civil War Medicine.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)