On Monday, the

staff of the NMCWM was fortunate to be allowed the afternoon off to view the

movie Lincoln. It was a field trip of sorts!

|

| Here is the staff in front of the theater. A big thank you goes out to George, Tom, and Katie for staying behind to keep the museum open while the rest of us saw the movie! |

I’d heard a lot

of good reviews about the movie, so I was eager to finally see it. Though I thought there were a couple of

instances that showed a definite Hollywood interpretation, I did enjoy it overall. There were even some short scenes that

touched on Civil War medicine, which justified our trip! I think my biggest disappointment was the

fact that the severed leg of General Sickles in its display case was shown

briefly in one scene, but was not identified.

What a great opportunity they missed in not mentioning that story!

Since there is so

much interest in Abraham Lincoln at the moment, I thought I’d share a few of

the Lincoln artifacts in the museum’s collection that are not currently on

display.

|

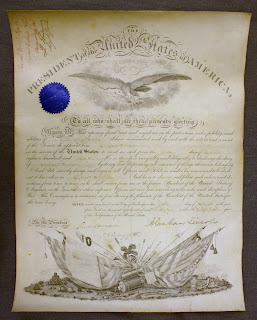

| Here is a Certificate of Commission for Dr. Elias J. Marsh, which bears the signature of President Abraham Lincoln, and is dated August 10, 1861. |

A letter in our

collection that was written by Civil War nurse, Clarissa Jones, on April 15th,

1865 about Lincoln’s assassination reads:

“I am unfit to write or even

think. I am utterly prostrated in mind

by the awful news of last evening—I am just starting out to try to get a paper

to send to you with this, fearing I may not succeed I will mention the terrible

calamity of which the paper gives a better def.

The Pres. was last night shot while in the

Theatre and died this A.M. at 7. Sec.

Seward was stabbed while in bed, and his son mortally stabbed by the same

man—he has since died—reports to the effect that Grant also was

assassinated….but it has not been confirmed—“ It shows the shock and grief many people felt

at the news of his assassination, as well as some of the rumors which

circulated.

|

| One of our more interesting Lincoln items is a replica of a plaster life mask made by Leonard Volk in 1860. |

A life mask is

made by applying plaster to a person’s face and letting it dry. Petroleum jelly or oil is put on the subject’s

face first, but there can still be some hair pulled out when the mask is

removed. Mr. Lincoln is said to have

commented that the process of removing the hardened plaster cast from his face

was, “anything but agreeable!” He was

reportedly pleased with the final product though. He had another life mask done about five

years later, and it is interesting to compare the two masks. The presidency and the war appear to have

aged him much more than five years. You

can see a short video about the two life masks here.

|

| Here is a cast of Lincoln’s hand which was done at the same time. The object he is clutching is a broom handle, and the hand next to the cast gives some perspective for the size of his hands! |

Though these

casts are interesting to study, I think I’d prefer to simply have a picture

taken!

Photos courtesy of the

National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

.JPG)