Part of my job here at the National Museum

of Civil War Medicine involves helping to tell the stories of the men and women who

were involved with medical care in the Civil War. Sometimes that is accomplished using their

personal belongings or their medical instruments and supplies. These things can certainly give insight into aspects

of their lives or the medical techniques and technology of the time, but it’s

not quite the same as being able to see the face associated with the

objects. I think it is far more

compelling to be able to show that these were real people in the stories that

we tell. So, today I thought I would

share the story and the image of one Civil War Surgeon.

At the start of the Civil War, Orange B.

Ormsby was a young physician in Greenville, Illinois. On June 25, 1861, at the age of 25, he

enlisted as a Private in the 22nd IL Infantry, Company E. His enlistment papers describe him as being

5’ 10” tall, with blue eyes, light hair, and a fair complexion. In August of that same year he transferred to

the 18th IL Infantry, Company S and was commissioned as an Assistant

Surgeon. His claim to fame was that during

the Siege of Corinth, he was working behind Confederate lines and assisted in

saving the life of General Richard Oglesby, who was wounded in the chest and

back. After the war General Oglesby went

on to serve three terms as the Governor of Illinois, and also served as a U.S.

Senator. The town of Oglesby, IL, is

named for him.

|

| An image of General Richard Oglesby from the National Archives and Records Administration. |

By 1863, Orange B. Ormsby had enlisted as

a Surgeon in the 45th IL Infantry, Company S, also known as the

“Washburn Lead Mine Regiment.” The 45th

IL was assigned to the Army of the Tennessee, and during his time with them

Ormsby would have been in battles in Mississippi, including the Vicksburg

Campaign. In fact, there are monuments

to the 45th IL Infantry in Vicksburg

On October 29, 1864, Ormsby was discharged

for disability (lumbago and rheumatism) and went home to his wife and family in

Illinois. He received an Army pension starting when

he was age 55 and died on June 13, 1899 at the age of 63. Another interesting note is that his youngest

son, Oscar Burton Ormsby, followed in his father’s footsteps by attending

medical school and serving in the medical corps in World War I.

Surgeon Ormsby’s CDV was donated to the

NMCWM by one of his descendants. He

shared the story with me of searching for Ormsby’s grave: I visited Murphysboro,

Illinois in 2004 and found his grave. An

invisible string led me to it as I had no prior indication where it was but was

led (by accident?) directly to it. I

went to the cemetery which was quite large and stopped at a random site, got

out of the car to survey the area and found I was inadvertently located next to

his plot. The hair on the back of my

neck was standing at attention! Perhaps

Orange’s spirit was helping me. I don’t

know but it makes a good story.

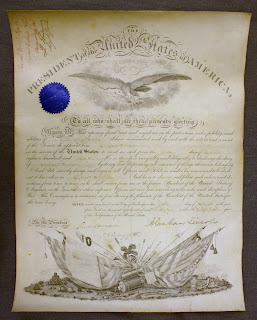

Though the CDV image is somewhat faded, we

still wanted to display it. In this

case, the best option was to digitize it.

The digitized image and a brief biography of Orange B. Ormsby are currently

a part of the NMCWM’s video display, “Faces of Civil

War Medicine.” This way Surgeon Ormsby’s

image and his story can be shared with the public, while the original CDV image

can be better preserved for the future.

I hope Orange’s story can be preserved this way as well!

Photos courtesy of the National

Museum of Civil War Medicine, except where otherwise noted.

*Note –

I will be taking a short break for the Christmas holiday, but I look forward to

sharing more blog posts with you in 2013.

Happy Holidays everyone!

.JPG)